Any Large Room Where Torah Scrolls Are Kept and Read Publicly Can Function as a

Delight note, No photography immune in the Shrine of the Volume

The Hebrew Bible is the cornerstone of the Jewish people and this key text has left its imprint on Christianity and Islam.

The exhibition at the Shrine of the Volume Complex represents a journey through time, which, adopting a scholarly-historical arroyo, traces the evolution of the Volume of Books. The upper galleries take the visitor from the oldest extant biblical manuscripts, which were discovered in the Judean Desert, through the story of the sectarians living at Qumran, who attempted to translate the biblical ethics embodied in these texts into a way of life. The lower galleries tell the remarkable tale of the Aleppo Codex – the most accurate manuscript of the Masoretic text and the closest to the text of the printed Hebrew Bibles used today.

The Shrine of the Volume was congenital equally a repository for the first 7 scrolls discovered at Qumran in 1947. The unique white dome embodies the lids of the jars in which the get-go scrolls were institute. This symbolic building, a kind of sanctuary intended to limited profound spiritual significant, is considered an international landmark of mod architecture. Designed past American Jewish architects Armand P. Bartos and Frederic J. Kiesler, it was defended in an impressive anniversary on April 20, 1965. Its location next to official institutions of the Israel—the Knesset (Israeli Parliament), key government offices, and the Jewish National and University Library—is advisable considering the degree of national importance that has been accorded the ancient texts and the building that preserves them.

The contrast between the white dome and the black wall alongside it alludes to the tension evident in the scrolls between the spiritual world of the "Sons of Light" (every bit the Judean Desert sectarians called themselves) and the "Sons of Darkness" (the sect's enemies). The corridor leading into the Shrine resembles a cave, recalling the site where the ancient manuscripts were discovered.

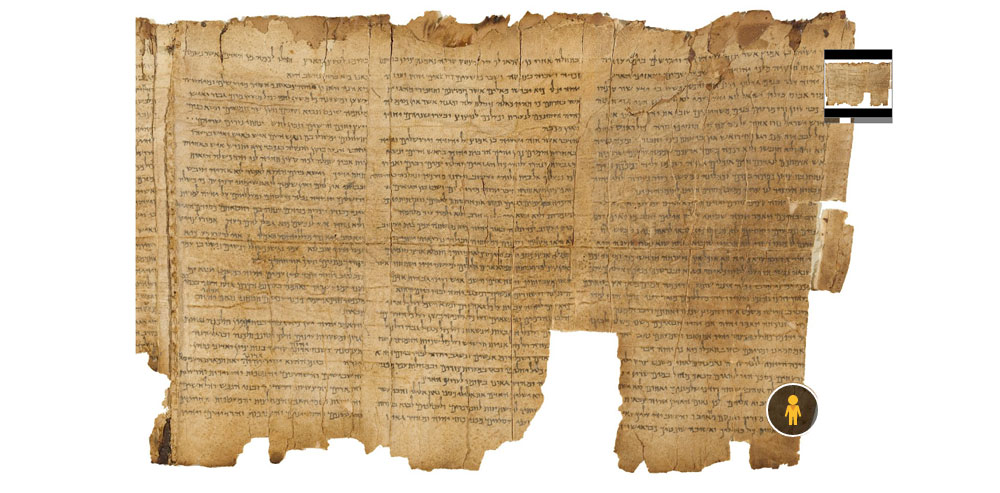

The Expressionless Sea Scrolls

The Dead Body of water Scrolls are aboriginal manuscripts that were discovered between 1947 and 1956 in xi caves most Khirbet Qumran, on the northwestern shores of the Dead Body of water.

They are approximately two thousand years former, dating from the third century BCE to the starting time century CE. Most of the scrolls were written in Hebrew, with a smaller number in Aramaic or Greek. Most of them were written on parchment, with the exception of a few written on papyrus. The vast bulk of the scrolls survived as fragments - but a handful were establish intact. Notwithstanding, scholars have managed to reconstruct from these fragments approximately 950 different manuscripts of diverse lengths.

The manuscripts fall into three major categories: biblical, apocryphal, and sectarian. The biblical manuscripts comprise some 2 hundred copies of books of the Hebrew Bible, representing the earliest show for the biblical text in the earth. Among the apocryphal manuscripts (works that were not included in the Jewish biblical canon) are works that had previously been known only in translation, or that had not been known at all. The sectarian manuscripts reverberate a wide variety of literary genres: biblical commentary, religious-legal writings, liturgical texts, and apocalyptic compositions. Most scholars believe that the scrolls formed the library of the sect that lived at Qumran. However it appears that the members of this sect wrote but part of the scrolls themselves, the rest having been composed or copied elsewhere.

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls represents a turning betoken in the written report of the history of the Jewish people in ancient times, for never before has a literary treasure of such magnitude come up to light. Thanks to these remarkable finds, our knowledge of Jewish society in the State of State of israel during the Hellenistic and Roman periods besides every bit the origins of rabbinical Judaism and early Christianity has been profoundly enriched.

Discovery of the Scrolls

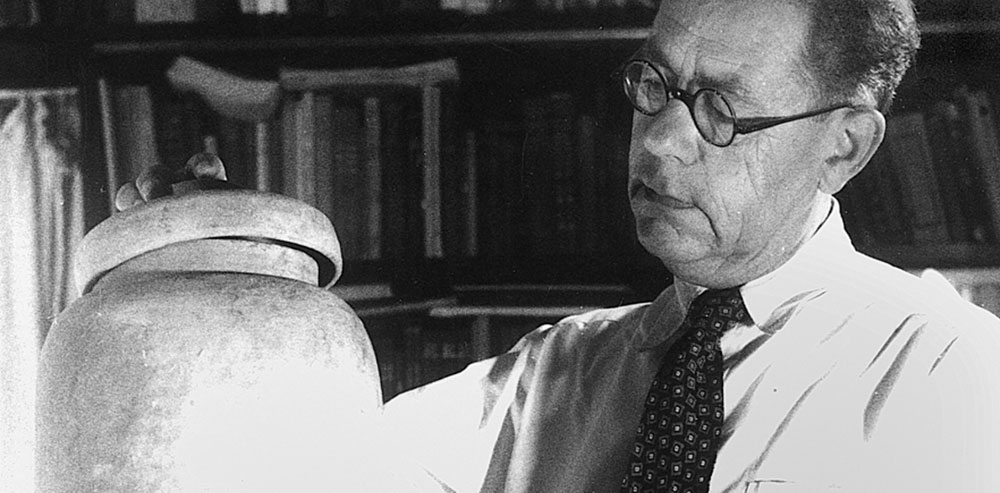

The first 7 Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered by chance in 1947 by Bedouin, in a cave well-nigh Khirbet Qumran on the northwest shore of the Dead Body of water. Three of the scrolls were immediately purchased by archeologist East. Fifty. Sukenik on behalf of the Hebrew University; the others were bought by the Metropolitan of the Syrian Orthodox Church in Eastward Jerusalem, Mar Athanasius Samuel. In 1948 Samuel smuggled the four scrolls in his possession to the U.s.a.; it was merely in 1954 that Sukenik'south son, Yigael Yadin, also an archeologist, was able to bring them back to this country.

Over the next few years, from 1949 to 1956, additional fragments of some 950 different scrolls were discovered, both by Bedouins and by a joint archaeological expedition of the École Biblique et Archéologique Française and the Rockefeller Museum, nether the direction of Professor Begetter Roland de Vaux. Since then, no further scrolls have come to low-cal, though excavations take been carried out from fourth dimension to time at the site and nearby.

Qumran Library

"They display an extraordinary interest in the writings of the ancients, singling out in particular those which make for the welfare of soul and trunk" (Josephus, Jewish War II, viii, 6).

The sectarians attached supreme importance to the study of the Scriptures, to biblical exegesis, to the estimation of the police force (halakha), and to prayer. The hundreds of scrolls discovered at the site and the rules of the Community preserved in them point that they took the biblical injunction, "Let not this Book of the Education cease from your lips, but recite information technology day and night" (Joshua 1:8), quite literally. Their laws enjoined them to ensure that shifts of community members be engaged in study around the clock, in order to reveal the "divine mysteries" of the law, history, and the creation.

The sectarians' scribal and literary activities apparently took identify in several rooms in the communal eye at Khirbet Qumran, mainly in the "scriptorium" on the upper floor. Most of the scrolls were written on parchment, with a small number on papyrus. The scribes used styluses fabricated from sharpened reed or metal, which were dipped into black ink – a mixture of soot, gum, oil, and water. Inscribed bits of leather and pottery shards establish at the site attest to the fact that they proficient earlier starting time the bodily copying work.

Virtually of the Hebrew and Aramaic scrolls found at Qumran were written in "Jewish" or square script, common during the Second Temple period. A few scrolls, all the same, were written in aboriginal Hebrew script, a very small number in Greek, and fewer still in a kind of secret writing (cryptographic script) used for texts dealing with mysteries that the sectarians wished to conceal. Scholars believe that some of the scrolls were written by the community scribes, just others were written outside of Qumran.

Biblical Scrolls

"Being versed from their early on years in the holy books [and] various forms of purification . . ." (Josephus, Jewish War II, viii, 12)

All the books of the Hebrew Bible, except for Nehemiah and Esther, were discovered at Qumran. In some cases, several copies of the same book were institute (for instance, there were thirty copies of Deuteronomy), while in others, but ane copy came to light (e.grand., Ezra). Sometimes the text is near identical to the Masoretic text, which received its final form about grand years later on in medieval codices; and sometimes it resembles other versions of the Bible (such equally the Samaritan Pentateuch or the Greek translation known as the Septuagint). Scrolls bearing the Septuagint Greek translation (Exodus, Leviticus) and an Aramaic translation (Leviticus, Job) have survived too.

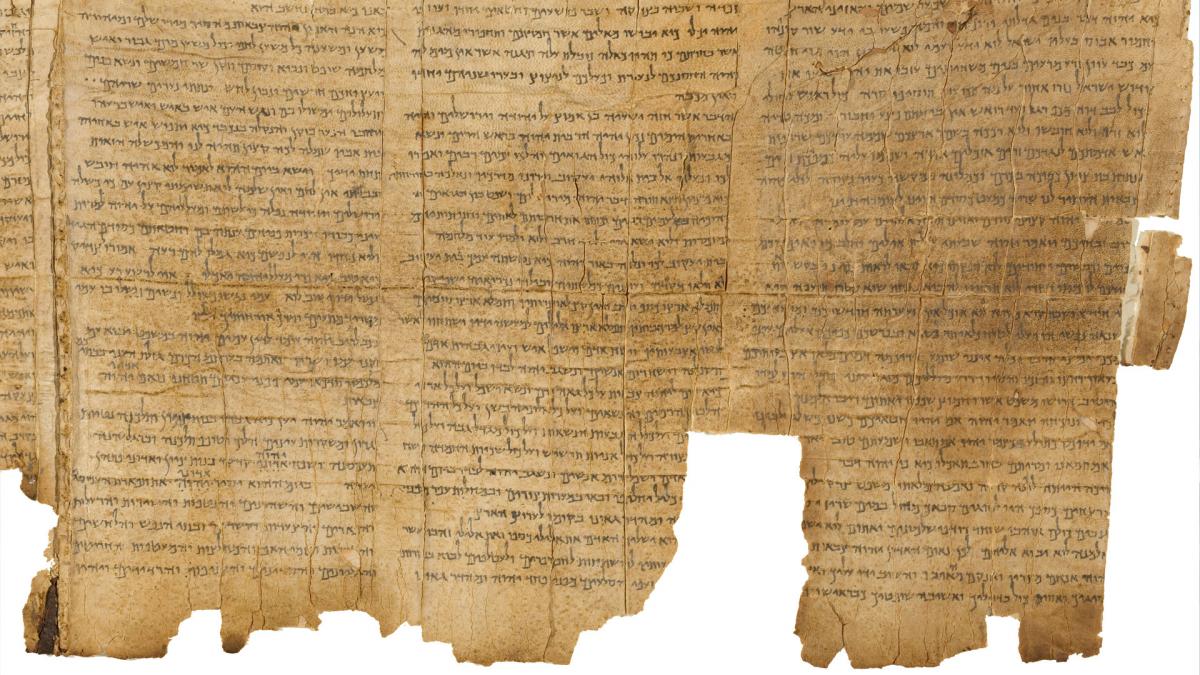

The almost outstanding of the Dead Bounding main Scrolls is undoubtedly the Isaiah Scroll (Manuscript A) – the only biblical scroll from Qumran that has been preserved in its entirety (it is 734 cm long). This whorl is likewise one of the oldest to accept been preserved; scholars estimate that it was written around 100 BCE. In improver, among the scrolls are some twenty additional copies of Isaiah, besides as six pesharim (sectarian exegetical works) based on the book; Isaiah is also ofttimes quoted in other scrolls. The prominence of this particular book is consistent with the Community's messianic beliefs, since Isaiah (Judean Kingdom, eighth century BCE) is known for his prophecies concerning the End of Days.

Apocrypha in the Scrolls

"Against them, my son, be warned! The making of many books is without limit" (Ecclesiastes 12:12)

As well the biblical books, at that place are many other literary works of the 2d Temple period which, for religious and other reasons, were forbidden to be read (in public?) and were therefore not preserved past the Jews. Ironically, many of these works were preserved by Christians. Counterfeit books such every bit Tobit and Judith were preserved in Greek in the Septuagint translation of the Bible, and in other languages based on this translation. Pseudepigraphical books (attributed to fictitious authors) were preserved equally independent works in a variety of languages. The Book of Jubilees, for example, survived in Ge'ez (classical Ethiopic), and the Fourth Book of Ezra survived in Latin.

These counterfeit and pseudoepigraphical books were cherished by the members of the Judean Desert sect. Prior to the discovery of the Dead Bounding main Scrolls, some of the books had been known merely in translation (such as the book of Tobit and the Testament of Judah), while others were altogether unknown. Among these are rewritten versions of biblical works (such as the Genesis Apocryphon), prayers, and wisdom literature. In some cases, several manuscripts of the same work were discovered, indicating that the sectarians highly valued these compositions and even considered a few of them (such every bit the Start Book of Enoch) as full-fledged "Holy Scriptures."

Sectarian Scrolls: The Pesharim

"Existence versed from their early years in . . . apophthegms of the prophets; and seldom if always do they err in their predictions" (Josephus Jewish State of war Ii, 8, 12)

The Bible was the basis for the intellectual and spiritual experience of the members of the Qumran Community, and the purpose of its estimation was in gild "to do what is expert and correct before Him as He commanded by the hand of Moses and all His servants the prophets" (Customs Rule 1:1–3). The exegetical works written by the sectarians deal with the interpretation of the laws of the Pentateuch (such every bit the Temple Scroll), of various biblical stories (such as the Testament of Levi), and, in particular, of the words of the Prophets.

The method of biblical estimation known as pesher is unique to Qumran. The pesharim may exist divided into two types: those dealing with a specific bailiwick (such as 4QFlorilegium), and those written every bit running commentaries. In pesharim of the second blazon, the biblical text is copied passage past passage in the original guild, and each passage is explained past turn. Most of the "running" pesharim, of which in that location are about seventeen, are based on books of the Prophets, such as Isaiah, Nahum, or Habakkuk; there is besides one pesher on the volume of Psalms, which the Community besides regarded as a prophetic work. The interpretations themselves are prophetic in nature and insinuate to events related to the period in which the works were composed (hence their importance for historical research). With a few exceptions, they proper noun no historical personalities, but utilize such expressions every bit "Teacher of Righteousness," "Priest of Wickedness," or "Man of Falsehood."

The Community Rule: The Sect's Code

"They live together formed into clubs, bands of comradeship with common meals, and never cease to conduct all their diplomacy to serve the full general weal" (Philo, Apologia pro Iudaeis 11.5)

Prior to the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the just testify of the Essenes' way of life was provided by classical sources (Josephus Flavius, Philo, and Pliny the Elder) and by a few allusions in rabbinic literature. The discovery of the scrolls allowed a rare starting time-hand glimpse of the lives of those pietists, through the "Rule" literature that governed their lives. This literature, later to evolve in a Christian monastic context, is unknown in the Bible, and its discovery at Qumran represents the earliest testimony to its existence.

The work known as the "Customs Dominion" is considered a fundamental to understanding the Community's way of life, for it deals with such topics as the comprisal of new members, rules of behavior at communal meals, and fifty-fifty theological principles. The picture that emerges from the curl is one of a community that functioned every bit a collective unit of measurement and pursued a severe ascetic lifestyle based on stringent rules. The coil, written in Hebrew, was found in twelve copies; the copy displayed in the Shrine of the Volume, which is almost complete, was discovered in 1947.

The Temple Scroll

"They shall not profane the city where I abide, for I, the Lord, abide amongst the children of Israel for ever and ever" (Temple Curl XLV: xiii–fourteen).

The Temple Scroll, which deals with the structural details of the Temple and its rituals, proposes a programme for a futurity imaginary Temple, remarkably sophisticated, and, to a higher place all, pure, which was to replace the existing Temple in Jerusalem. This plan is based on the plan of the Tabernacle and of Solomon and Ezekiel'south Temples, but it is also influenced by Hellenistic architecture.

The coil is written in the style of the book of Deuteronomy, with God speaking as if in first person. Some government consider it an alternative to the Mosaic Law; others, a complementary legal estimation (midrash halakha). This work combines the various laws relating to the Temple with a new version of the laws set out in Deuteronomy 12–23. Its author probably belonged to priestly circles and composed information technology at a time earlier the Customs left Jerusalem for the desert, in the 2d half of the second century BCE. Information technology was evidently written against the background of the controversy centering on the Temple in Jerusalem.

Prayers, Hymns, and Thanksgiving Psalms

The profoundly religious, reclusive customs living at Qumran devoted all its energies to the worship of God. The sectarians believed that the angels were their companions and that their spiritual level elevated them to the border between the human and the divine. The temper of sanctity that enveloped them is axiomatic from the ane hundred biblical psalms and more than two hundred actress-biblical prayers and hymns preserved in the scrolls. Most of the latter were previously unknown; they include prayers for unlike days (even the Cease of Days), magical spells, and so forth.

Among this affluence of literary texts is a unique genre of hymns called hodayot or "Thanksgiving Hymns," on the basis of their stock-still opening formula, "I thank Thee, O Lord." Scholars take divided the eight manuscripts of the Thanksgiving Hymns into two chief types: "Hodayot of the Teacher," in which an individual (the sect'south "Teacher of Righteousness"?) thanks God for rescuing him from Belial (Satan in the sect's writings) and the forces of evil, and for granting him the intelligence to recount God's greatness and justice; and "Hodayot of the Customs," hymns concerned with topics relevant to the Customs as a whole. Both types extensively apply such terms as "mystery," "appointed time," and "light" and express ideas characteristic of the Community's beliefs, such as divine love and predestination.

The End of Days: The "War of the Sons of Light and the Sons of Darkness"

"This is the 24-hour interval appointed past Him for the defeat and overthrow of the Prince of the kingdom of wickedness" (War of the Sons and Light and the Sons of Darkness XVII:5–6)

The members of the Community of the yahad retired to the desert out of a profound confidence that they were living in the End of Days and that the final Day of Judgment was close at mitt. They believed that all the stages of history were predetermined past God, and thus any endeavor past the forces of the "Prince of Darkness" and "all the government of sons of injustice" to corrupt the "Sons of Righteousness" was destined to fail; salvation would ultimately arrive, as nosotros read in Pesher Habakkuk (VII:xiii–14): "All the ages of God reach their appointed end as He determines for them in the mysteries of His wisdom."

The sectarians divided humanity into two camps: The "Sons of Light," who were good and blest by God – referring to the sectarians themselves; and the "Sons of Darkness," who were evil and accursed – referring to everyone else (Jews and gentiles alike). They believed that in the Stop of Days these two camps would battle each other, as described in item in the scroll now known every bit "The State of war of the Sons of Light and the Sons of Darkness." This piece of work, which provides a detailed account of the mobilization of troops, their numbers and division into units, weaponry, and so forth, states that at the stop of the 7th round of battles, the forces of the "Sons of Light," aided by God Himself and His angels, would vanquish the "Forces of Belial" (as Satan is chosen in the sect's writings). Only then would the members of the Community be able to return to Jerusalem and engage in the proper worship of God in the futurity Temple, which would encounter with the stringent requirements set out, for example, in the roll known as "The New Jerusalem."

A Wandering Bible: The Aleppo Codex

1 of the greatest spiritual revolutions in human history was launched toward the end of the First Temple period, when the Jewish people began to shape their ancient traditions into holy scriptures. This process gathered momentum particularly after the destruction of the Temple and the Babylonian exile in the late 6th century BCE and culminated in the first centuries CE with the canonization of the corpus of sacred books we at present call the Hebrew Bible, which paved the mode for both the New Testament and the Koran. By virtue of this contribution to human culture, the Jewish people came to exist known every bit "the People of the Volume."

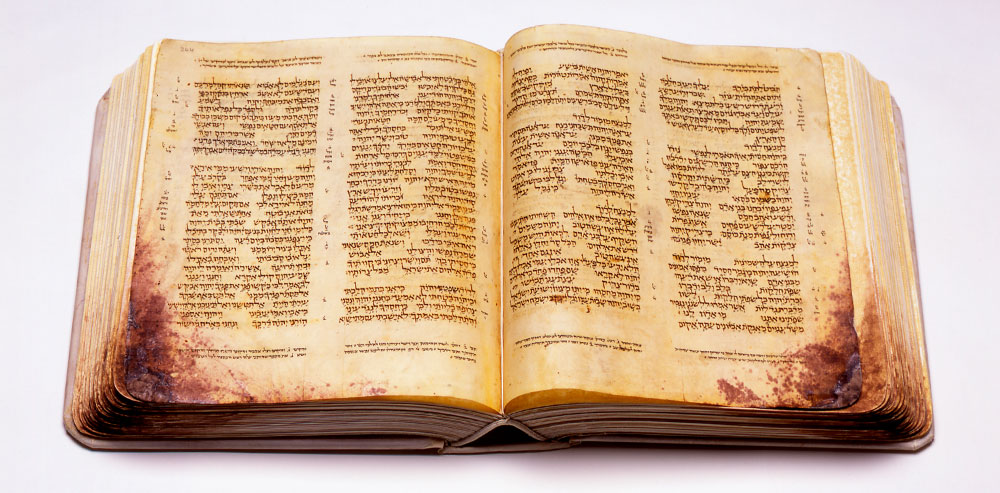

The "Aleppo Codex," considered the well-nigh accurate manuscript was written in Tiberias in the tenth century CE. Its text embodies traditions of pronunciation, spelling, punctuation, and cantillation handed downward through the generations and finally committed to writing in Tiberias past scholars known equally the "Masoretes." From Tiberias the book was taken to Jerusalem, to Egypt, and finally to Aleppo, Syrian arab republic; it was smuggled back to Jerusalem in the 1950s. The exhibition of the Aleppo Codex in the Shrine of the Book may be seen as a fulfillment of the words of the prophet Isaiah (2:3): "For pedagogy [Torah] shall come up forth from Zion, the give-and-take of the Lord from Jerusalem."

From Sacred Books to Catechism

The Bible tells united states that during the reign of Josiah, King of Judah (639–609 BCE), the high priest Hilkiah constitute "a scroll of the Law" (an early version of the book of Deuteronomy?) in the Temple. This event is commonly regarded as the primeval testify for the revolutionary process through which the aboriginal traditions of the Jewish people became sacred books, the most authoritative source for religious belief and practice. Scribes and priests among the Jewish exiles in Babylonia furthered this process by collecting the ancient traditions of the Bible, committing them to writing, and editing them; during the Western farsi period (ca. fifth century BCE), the kickoff corpus of sacred books came into being, known as the "Torah [or Law] of Moses" (the Pentateuch?).

Some other landmark in the canonization of the Hebrew Bible is documented in the opening passage of the book known every bit The Wisdom of Ben Sira (or Ecclesiasticus), written around the yr 132 BCE. In this passage, the phrase "the police force and the prophets and the other writings" occurs three times, indicating that a second corpus of sacred scriptures – namely, the Prophets – was already known at that time. Eventually, other books (such equally Psalms and Job) were "promoted" to a level of sanctity, while others (including The Wisdom of Ben Sira) remained outside the canon, either surviving as apocryphal literature or disappearing altogether. The canonization process came to an end in the starting time centuries CE, when the Hebrew Bible received its final class.

From Curl to Codex

Comparison of the biblical scrolls discovered at Qumran has shown that several versions of the biblical text were in utilize among the Jews, but that one of them, known to scholars as the "pre-Rabbinic" or "pre-Masoretic" text, was held in detail regard (accounting for some 40% of the scrolls). Toward the stop of the Second Temple menstruum, this version came to be seen as authoritative by mainstream Judaism, as indicated by the fragments of later biblical scrolls discovered at Masada, Wadi Murabba'at, Nahal Hever, and Nahal Ze'elim, all of which follow that text. From the fourth dimension of these scrolls until the 8th century CE, the period to which the earliest biblical manuscripts from the Cairo Genizah have been ascribed, no Hebrew manuscripts of the Bible have been preserved (some of the biblical fragments from the Cairo Genizah were written according to the authoritative version mentioned above). Evidence of the biblical text from the 4th to 8th century CE has been preserved merely by Christians – in Greek, Latin, and other translations.

Translations of the Bible were circulated in the form of "codices" (sing. codex), such equally the 4th-century CE Codex Sinaiticus, which were written on leaves of parchment folded and sewn together in a binding. This technological innovation made it possible to utilize both sides of the folio for writing and to leaf through the manuscript easily. Information technology was simply in the 8th century CE, nevertheless, that Jews began to adopt this method, and even then, merely for the purposes of report and interpretation. Books read as part of the obligatory synagogue service (such equally the Pentateuch and the Book of Esther) were still written, every bit required by tradition, on scrolls; the text appearing on the scrolls consisted just of consonants, without vocalization or punctuation. The shift from scroll to codex made it possible, for the beginning time, to tape in writing all the instructions for copying and pronunciation – the Masorah – which had until then been transmitted orally from one generation to the next.

The Nativity of the Aleppo Codex

The Aleppo Codex, known every bit the keter (crown) in Hebrew or the taj in Arabic – a title of honor given to select aboriginal manuscripts, mainly in Eastern countries – was written at the beginning of the tenth century CE. Its colophon (an inscription placed at the end of a manuscript), copied by Professor Umberto Cassuto when he visited Aleppo in 1943, states that the manuscript, which comprised all twenty-four books of the Bible, was copied in the land of Israel by a scribe named Solomon ben Buya'a, scion of a well-known family of scribes who specialized in copying biblical manuscripts; the vocalization, cantillation marks, and masoretic comments were added past Aaron ben Asher, the last of the Masoretes and the final link in this great chain of tradition.

The Aleppo Codex is considered to be the most accurate existing manuscript of the Masoretic text (another well-known manuscript is the Petrograd Codex of 1009). Its text is practically identical to the pre-Masoretic version of the biblical text that has been preserved in some of the biblical scrolls found at Qumran (approximately one m years older than the Codex) and the somewhat later scroll fragments constitute at Masada and the vicinity, as well every bit some of the biblical fragments discovered in the Cairo Genizah. The Codex originally contained between 480 and 490 leaves, but, unfortunately, only 295 of them have survived, representing some three-quarters of the Bible.

We do not know who commissioned the Aleppo Codex. We do, however, know from the colophon that it was purchased, many years afterward its completion, by a wealthy Karaite of Basra, Republic of iraq, named Israel Simhah, who donated it to the Karaite synagogue in Jerusalem. In the late 11th century CE it was smuggled out of the land, either by Seljuks in 1071 or past Crusaders 1099, and offered for sale in Egypt.

The Craft of the Medieval Scribe

In the Eye Ages, scribes worked seated on the floor or on a mattress, with a board laid over their knees equally a working surface. The text was either dictated or copied from another book. To avoid making mistakes, the scribes would pronounce the words aloud earlier writing them. The texts were copied onto parchment or papyrus, and subsequently also onto paper, using a stylus or quill dipped into ink. Other pieces of equipment included a knife for marking the lines and columns and piercing holes, scissors for cutting the parchment, a case to hold the writing implements, and an inkwell.

Ceremonial Objects of the Jewish Community of Aleppo

The rich artistic tradition of the Jewish community of Aleppo is notable in its formalism objects, which were donated by the members of the community to the synagogue to marking special occasions in their lives. The objects include Torah cases, crowns, elaborate silverish finials, and oval plaques (breastplates) with dedicatory inscriptions, all on display in the lower gallery of the Shrine of the Volume. Similar plaques were too attached to the curtains (parokhot) in forepart of the Torah shrines. The inscriptions are fascinating historical documents, which reveal the personal stories of members of the customs and enable us to reconstruct some of the long-forgotten details of Aleppine Jewish life.

Maimonides and the Aleppo Codex

After the Aleppo Codex was smuggled into Egypt, it was bought by the local Jews and deposited in the synagogue of the Jerusalem Jews in ancient Cairo. Co-ordinate to tradition – and modern scholarship – the cracking philosopher and legal (halakhic) authorisation Maimonides (1138–1204) relied on the Aleppo Codex when he formulated the laws relating to Torah scrolls in his legal code, the Mishneh Torah, equally he explains in the determination to that department: "In these matters we relied upon the codex, now in Egypt, which contains the twenty-4 books of Scripture and which had been in Jerusalem for several years. It was used as the standard text in the correction of books. Everyone relied on it, because it had been corrected by Ben Asher himself, who worked on its details closely for many years and corrected it many times whenever it was being copied. And I relied upon information technology in the Torah scroll that I wrote co-ordinate to Jewish Police" (Sefer Ahavah, Hilkhot Sefer Torah 8:4). Maimonides' praise of the Aleppo Codex further enhanced the reputation of the venerated manuscript.

From Arab republic of egypt to Aleppo

At the end of the 14th century, the Aleppo Codex was brought from Egypt to Aleppo, Syrian arab republic, and placed in the "Cave of Elijah" in the city's ancient synagogue, in a metal chest sealed with a double lock, far from public view. The Jews of Aleppo saw the Codex every bit the most important manuscript in their possession – and so much and then, that judges were sworn in with it, and magical, protective powers were attributed to information technology. Information technology was strictly forbidden to sell the Codex or even remove information technology from the synagogue, as written on the title page, "Sacred to the Lord. . . . It shall exist neither sold nor redeemed. . . . Blessed exist he who guards information technology, accursed be he who steals it . . . ." The members of the community believed that if this injunction were violated, they would be severely punished.

Besides the Aleppo Codex, the Jewish community of Aleppo owned three other of import codices. One of them, known as the "Modest Codex," was probably written in Italy in 1341 by an Ashkenazi scribe. Its main part comprises the Pentateuch, with vocalization and cantillation marks and an Aramaic translation. Masoretic notes are inserted betwixt the columns, and Rashi'south commentary appears in the upper and lower margins. The Pocket-size Codex also includes an additional text of the Pentateuch in tiny Hebrew messages – without the translation, vocalization, and cantillation marks – also equally the Vocal of Songs with Rashi'southward commentary, the V Scrolls, the sections from the Prophets read in the synagogue after the Torah reading (haftarot), and a commentary (midrash) on the Masorah. It is currently on display at the Shrine of the Volume.

The Fame of the Aleppo Codex

The fame of the Aleppo Codex spread far and wide, and generations of scribes consulted it in order to obtain administrative answers to their textual queries. In 1599 Rabbi Joseph Caro of Safed, author of the legal lawmaking Shulhan Arukh, sent a copy of the Codex to Rabbi Moses Isserles (the "Rema") in Cracow, who used it to write his own Torah scroll. Among the many "pilgrims" to Aleppo to examine the Codex, we know of Yishai Hakohen b. Amram Hakohen Amadi of Kurdistan, who visited Aleppo at the end of the 16th century; Moses Joshua Kimhi, who traveled to Aleppo on the instructions of his begetter-in-law, Rabbi Shalom Shakhna Yellin (1790–1874), a renowned scribe; and Professor Umberto Cassuto, whom the Aleppo community permitted to consult the Codex in 1943, prior to the publication of a disquisitional edition of the Bible by The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Not only Jews were fascinated past the historic manuscript: Sometime earlier 1753, a British traveler named Alexander Russell received permission to view the Aleppo Codex; a facsimile of one of the pages of the Codex appears on the title page of a volume published in 1877 past a scholar named William Wickes; and in 1910 a missionary named J. Segall published a photographic reproduction of two pages of the manuscript – those containing the Ten Commandments – in his book, Travels through Northern Syria.

The Aleppo Codex Disappears

On December 1, 1947, two days later the adoption of the UN Security Council resolution to found the Land of Israel, anti-Jewish riots broke out in Arab countries. The aboriginal Aleppo synagogue was as well targeted. Later on it had been destroyed, information technology was rumored that the Aleppo Codex kept at that place had been desecrated and burned; Professor Cassuto wrote in Haaretz on January ii, 1948: "Keter Aram Zova, as information technology was called, is no more."

Saving the Aleppo Codex

Believed to be lost, the Aleppo Codex nevertheless rose from the ashes. When the riots had died down, it turned out that the Jews of Aleppo had managed to retrieve and hibernate information technology. Some ten years later, in 1958, the Codex was brought to Jerusalem in a bold clandestine performance, made possible through the intervention of President Yizhak Ben-Zvi of Israel and various rabbinical leaders. The Aleppo Codex was entrusted to the Ben-Zvi Plant in Jerusalem, and a board of trustees, which included the Sephardi chief rabbi (the Rishon le-Zion), was appointed to look after it. It remained at the Ben-Zvi Institute for a while, and later was on display at the National Library before finally arriving at the Israel Museum.

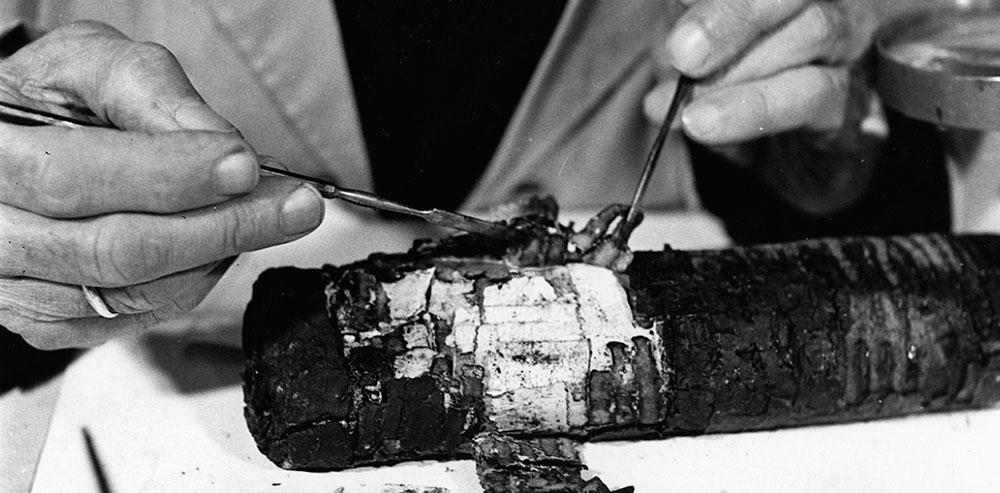

Unfortunately, the Codex that reached Jerusalem was no longer consummate – the beginning, the end, and a few pages from the middle were missing. Considering of its poor concrete condition, extensive restoration was necessary; this was carried out in the Israel Museum laboratories over a period of some ten years. Pieces of tape stuck to the Codex were removed, stains were cleaned, and the ink was reinforced where it had disintegrated and peeled off. Considerable efforts were made to locate the lost parts, for it was rumored that they however existed somewhere. These efforts have non been very successful. To date, only one complete page, with a passage from the Book of Chronicles, was discovered in NY in 1981. It was brought to Israel, and is now owned by the State of israel Museum. In add-on, a minor fragment of a page from Exodus was kept as an amulet in the wallet of a fellow member of the Aleppine community in New York. Information technology too is now owned by the Israel Museum. Only fourth dimension will tell if any other leaves of the Codex still exist.

The Aleppo Codex as a Symbol

Once the Aleppo Codex had left Aleppo and reached Jerusalem, the atmospheric condition under which it was kept changed completely. In Aleppo it had been enveloped in an aura of mystery and kept in a locked chest, far from the public eye. In Jerusalem, however, in the Shrine of the Book, it is on public view. Many printed editions of the Bible base their texts on the Aleppo Codex: The disquisitional edition being published by the Hebrew University Bible Project; the scientific edition being published by Bar-Ilan University – Mikra'ot Gedolot "Haketer," which includes the Masorah Parva and Masorah Magna from the Aleppo Codex; and, most recently, a new edition of the Hebrew Bible inspired by the Aleppo Codex, entitled Keter Yerushalaim (Jerusalem Crown).

After some i one thousand years of wandering, the Aleppo Codex has reemerged in Jerusalem. It is at present on display together with the Dead Body of water Scrolls – they likewise were "brought to life" after ii millennia. Interestingly, iii of the scrolls were purchased by Professor Sukenik simply a few days before the synagogue in Aleppo was burned This unique symbolism enhances the significance of the Shrine of the Book, whose very form represents the idea of the rebirth of the Jewish people afterward two g years of wandering, exile, and near-anything; to quote the prophet Ezekiel in his "Vision of the Dry Basic" (37:14): "I will put my breath into you lot and you shall live once more. . . ."

"They shall not profane the city where I abide, for I, the Lord, abide amongst the children of Israel for ever and ever" (Temple Curlicue XLV:xiii–14).

Explore the Dead Sea Scrolls Online

The Isaiah Scroll on a Timeline

Travel back in time and find the history of the scroll

The Digital Expressionless Sea Scrolls

Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Project, allowing users to examine and explore these virtually ancient manuscripts from 2d Temple times at a level of particular never before possible. Developed in partnership with Google, the new website gives users access to searchable, fast-loading, high-resolution images of the scrolls, as well as curt explanatory videos and background data on the texts and their history.

Explore the Isaiah Scroll

The Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaa) is one of the original seven Dead Sea Scrolls discovered in Qumran in 1947. It is the largest (734 cm) and best preserved of all the biblical scrolls, and the just one that is nigh complete.

Visualizing Isaiah

Visualizing Isaiah invites yous on a journey through a rich selection of objects from the Museum'south collections that portray the era of the Prophet Isaiah.

Human Sanctuary

The Human Sanctuary is a web based, interactive, encyclopedia offering a unique glimpse into community life during the historical menstruum at the beginning of the Mutual Era (CE)

Time Travel: The Story of the Dead Sea Scrolls

Animated Film

Join Alma on a journey through time to detect the incredible story of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Hebrew with English subtitles)

In memory of Uri Whistler In cooperation with George Blumenthal, USA

Screening every one-half 60 minutes during Museum opening hours

Dr. Adolfo Roitman, Lizbeth and George Krupp Curator of the Dead Sea Scrolls and Caput of the Shrine of the Book

williamsackelvel60.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.imj.org.il/en/wings/shrine-book/dead-sea-scrolls

0 Response to "Any Large Room Where Torah Scrolls Are Kept and Read Publicly Can Function as a"

Postar um comentário